Sometimes biases can be trivial, like preferring the color blue over orange. Other times, they can significantly impact people’s lives and careers, often negatively for those who are women and non-white. Last year, a report by the Center for Talent Innovation found that 71% of leaders select proteges who are of the same gender and race.

“What does that mean for how we reinforce what leadership looks like?” asked Pamela Fuller, Thought Leader of Inclusion & Bias at FranklinCovey, a management consulting firm. For instance, is there really a correlation between being a 6-foot tall man and having the competence to run a company, or is that a bias at play?

These biases not only impact the people on the receiving end — the employee who is consistently passed over for promotions, or the team member whose name is constantly mispronounced — but the organization as well. Biased behavior harms employee performance and the diversity, equity and inclusion of a workplace, which ultimately impacts agency performance.

At the 2020 NextGen Government Training Summit in August, Fuller unpacked what unconscious bias means, how it can negatively impact agency performance and how to overcome it by reframing biased thinking.

1. Everyone has biases.

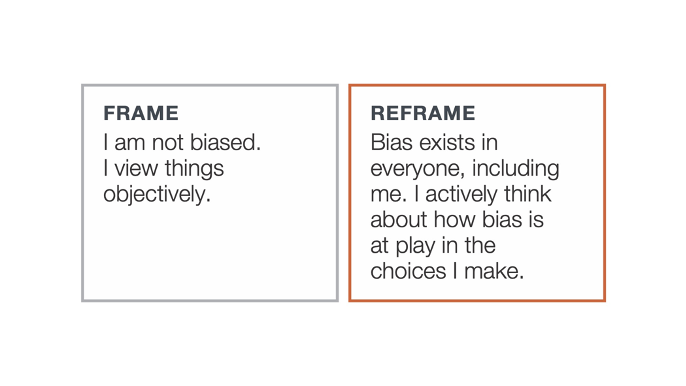

It’s frankly impossible to assume you are not biased if you are human. Fuller said our biases are formed from the content we consume, the education and training we receive, our cultures, our born preferences and all our lived experiences. To become aware of these unconscious biases requires self-reflection.

“If we can do some work on our own identifiers and use those to build the origin stories of our bias, those origin stories can give us insight into why we think a thing,” Fuller said.

2. Unconscious bias is not conscious bias.

The term “unconscious bias” may have become a little conflated as more people talk about it. The difference is whether you are aware of it or not.

“People might say, ‘I have unconscious bias against women in leadership.’ Well, once you state that, that is no longer an unconscious bias,” Fuller pointed out.

The process of taking it from unconscious to conscious is an important step that comes about through self-reflection and others’ input.

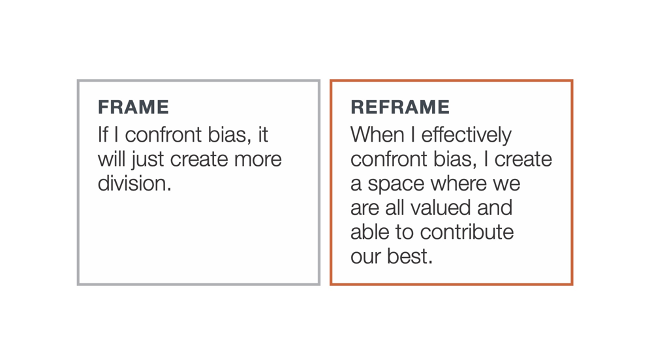

3. Avoiding bias doesn’t stop division.

Since when has avoiding the elephant in the room made it go away?

Since when has avoiding the elephant in the room made it go away?

It’s easy to believe that discussing bias around any identifier, such as race for example, would create more divisiveness in an office. If we bring it up, it’ll create more disunity. But what Fuller points out is that confrontation doesn’t create more disunity; it unearths it.

“We might be avoiding conflict, but we’re not actually avoiding division,” Fuller said.

As whole people, we bring all the facets of our identity to work, whether we log into a computer or walk through the office doors, Fuller added. That means we bring all our biases to work as well. Organizations need to effectively address bias by approaching it strategically, just like any other business initiative is approached. Ignoring it doesn’t mean it disappears.

“When we talk about process improvement, achieving results, executing on our budgets and fulfilling mandates, we don’t get to say, ‘That’s too hard. We’re not going to do that,’” Fuller said.

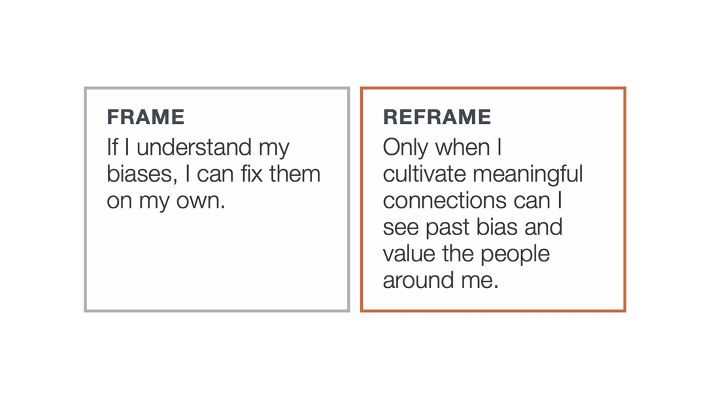

4. You can’t fix your biases on your own.

In the absence of information, our brains tend to create stories for the gaps. That’s why in overcoming unconscious biases, it’s critical to be intentional in cultivating meaningful connections with other people, Fuller said. These meaningful connections can complicate potential biases in a good way.

In the absence of information, our brains tend to create stories for the gaps. That’s why in overcoming unconscious biases, it’s critical to be intentional in cultivating meaningful connections with other people, Fuller said. These meaningful connections can complicate potential biases in a good way.

Our brains are supercomputers that process 11 million bits of information at a time. In other words, they have a capacity problem, and it’s not a good idea to try and follow your gut — or your “reptilian brain” as Fuller put it — when it comes to making decisions about people. This is especially true in areas like hiring, where gut-based decisions can drive away the most qualified candidates for the sake of imaginary comfort or so-called “fit.” These decisions ultimately come at the expense of the agency.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.