This blog post is an excerpt from GovLoop’s recent guide “State and Local Government: 8 Tech Challenges and Solutions.” In it, we provide an overview of case studies from governments across the country. Download the full guide here.

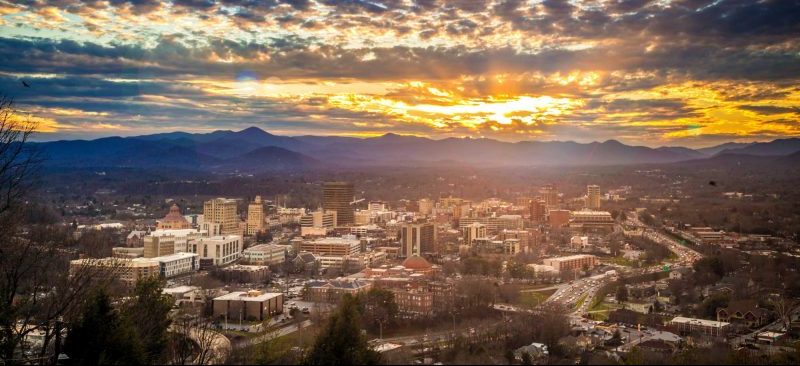

An interview with Eric Jackson, Digital Services Architect, Asheville, North Carolina

Challenge: Providing Context Around Open Data

You don’t have to look far for government websites dedicated to making data publicly accessible.

Many of these open data portals were launched with much fanfare, as a clear indication of government’s commitment to openness and transparency. But the cities and states leading this effort soon learned they had to fine-tune their approach to ensure everyday citizens could access data and make sense of it.

“One of two things happen when you put data out there,” said Eric Jackson, Asheville, North Carolina’s Digital Services Architect. “One of the things that happens is nobody uses it and nobody cares. That happens far too often. It’s one of the reasons why you want to actually think about what data’s useful and maybe engage with people who might use it before you bother putting it on your open data portal.

“The other possible outcome is that they will use it,” he said. “When people outside the city use city data, they sometimes use it to challenge what the city is doing — as they should.” When that happens, the question becomes how communities can use data to shape constructive conversations about important issues, especially contentious topics.

That was a reality Jackson and other Asheville employees had to address recently, when a local data activist combined city data with public records requests to draw attention to police arrests among the city’s homeless population.

The findings led to a highly contentious debate that played out in the newspapers and in front of the Asheville City Council.

“The reality is when the data gets out there, people in the public have the ability to work with that data and do analyses,” Jackson said. “And if what they’re doing is looking at parking data, or even budget data, then everybody says, ‘Yeah, that’s great.’ But when it starts to get into things like homelessness and policing, emotions get higher.”

The situation is further complicated when users don’t have the proper context around the data and are left to decipher it on their own, often drawing inaccurate or incomplete conclusions. But Jackson is hoping to change that by powering constructive conversations with data.

Solution

“What we ended up doing was bringing all the parties together, both internal and external,” Jackson said. “We had officers there from the police department and homelessness advocates and data activists and facilitated a conversation around … what the different perspectives were.”

One of the action items that came out of the meeting was the need to release general data about homelessness in Asheville. That information included point-in-time counts showing the size of the homeless population at a given time, how many people are sheltered and unsheltered, enrollment numbers for homeless programs, a general overview of the data sources and more. For now, the data is updated monthly because that’s how often Jackson’s team gets updates from external sources.

“Homelessness data is one of the areas where there are a lot of restrictions on what you can do because of privacy issues,” Jackson said. “But we basically committed to getting a dashboard up that would provide some grounding and context around homelessness that would at least give that basic [data].”

The city used a similar dashboard approach to release budget data and information about capital projects.

Whenever possible, the city uses an open process to develop its dashboards, meaning the public can view the software code in a public repository and see the live dashboard while it’s being developed.

When projects are developed in the open, it changes things, Jackson said. “You consider yourself always under scrutiny, and that’s not a bad thing.” It also provides a way for government to bring the public into the fold from the beginning.

The dashboards were designed to be user-friendly and easy to update so that the technology changes as the conversations change.

“This is very much a work in progress because we don’t see this as the answer to a question,” Jackson said of the dashboards. “We see it as one of the tools we use to support and facilitate conversations.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.