![]()

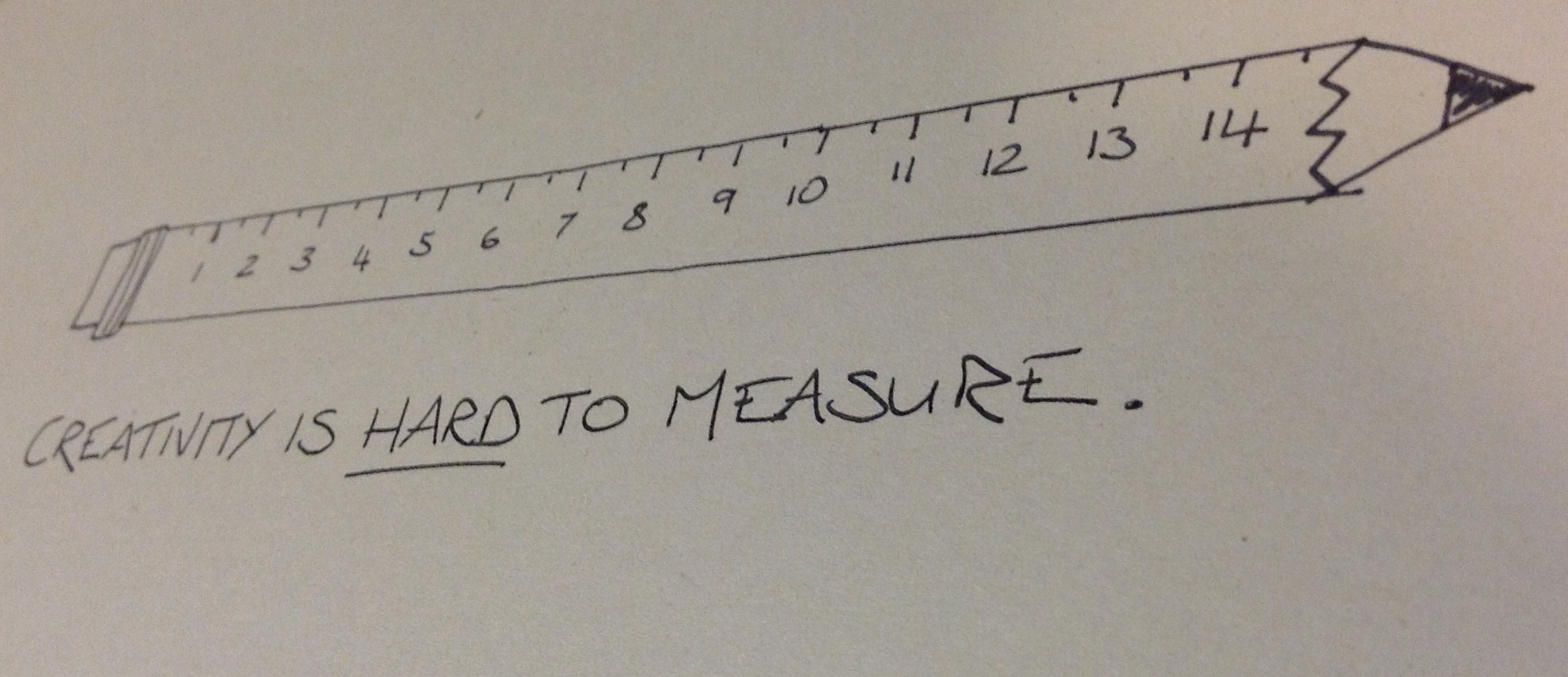

So, we’re working to increase the creative capacity of the Scottish Government (more about that in a previous post). But how do we know when we’ve actually done that? Well, that’s a very good question, I’m glad you asked.

The measurement of creativity is challenging, not least because of the number of elements that support a creative culture within an organisation. In fact, it feels a bit like nailing jelly to a herd of cats (OK, I’m mixing my analogies a bit there, and attempting to attach any kind of tasty dessert-type treat to one or more moggies, is not something I would ever advocate, but you get my meaning).

Let’s break it down a bit. We can divide potential creativity measures into three main categories:

- The conditions that foster creativity and innovation

- Creative activity

- The outcomes of creativity

We’ll explore the first of these in this post and pick up 2 and 3 next week.

Measuring the conditions that foster creativity and innovation

Our ‘Key Insights’ research suggested a number of recurring themes in relation to the organisational factors that, working in combination, foster creativity and innovation. The research also suggested types of indicators that we might measure in relation to these factors.

1. Organisational prioritisation of the creative process

- Is this is an organisation that is committed to creativity and innovation?

- Is the organisation clear about the outcomes that it wants from creativity and innovation?

- Are creativity and innovation rewarded in performance management?

- To what extent does the organisational culture accept and learn from failure without blame?

- Do informal organisational norms allow innovators to promote change, or will this kind of behaviour impact negatively on them?

- Is there enough scope to be innovative in the delivery of work (eg, is there ‘space’ to innovate, or are delivery mechanisms prescribed)?

- Does the organisation allow innovation through outcomes rather than outputs?

- Do organisational rules allow for fast-paced change, or are there significant hurdles to overcome at each stage of the process?

- Do organisational rules allow people to challenge the status quo and initiate innovation?

- Are there systems in place to collect ideas from staff, members of the public and other stakeholders?

- Does the organisation actively participate in forums to exchange ideas with other organisations?

- What is the investment (time, money, staff) in creativity and innovation? This might include consumer or market research, research and development (R&D), consultancy and collaboration programmes with universities or other external research units and skills training.

2. Staff: skills, capability, etc

- Do staff have the skills and confidence to innovate?

- Do enough staff have the skills in using tools and techniques to generate ideas and manage their translation into public value? If not, are resources available to secure these skills?

- Is there sufficient ‘risk capital’ to support innovation?

- Average change in personnel numbers.

- Number of training sessions related to innovation hosted by the organisation, as a percentage of total sessions.

3. Technological infrastructure (including access to and use of ICT)

- ICT expenditure as a percentage of administrative costs.

- Website and intranet expenditure as a percentage of total ICT expenditure.

- Average age of ICT equipment.

- Replacement time for ICT equipment.

4. Staff and stakeholder perceptions

The evidence indicates a link between employee engagement and organisational performance, with creativity and innovation part of the overall picture of ‘performance’ (see, for example, MacLeod and Clarke, 2009). Thus, improving employee engagement might be expected to lead to greater creativity. Trends in staff survey results over time might, therefore, provide a measure of whether the organisation is improving in terms of displaying (some of) the characteristics of a creative organisation.

But often there will be no ‘objective’ measure of the organisational conditions that foster creativity and innovation. For example, to answer the question ‘Is there enough scope to be innovative in the delivery of work?’, realistically, the best way for us to measure this may be to ask people what their views are on this issue.

Even where more ‘objective’ measures are available, people’s views are important as it is often the case that ‘perception is reality’ when it comes to determining how people actually behave. For example, if staff, stakeholders and the public do not feel that their ideas are valued (even if we had other evidence to indicate that their views are actually valued), then they are unlikely to make the effort to put their views forward.

Other measures

Next week, we’ll have a look measuring creative activity and outcomes. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Have you attempted to measure creativity in your organisation? If so, how did you go about it?

References

MacLeod, D. and Clarke, N. (2009). Engaging for success: enhancing performance through employee engagement. London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. [Accessed on 1 February 2015 from http://www.engageforsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/file52215.pdf]

Lesley Thomson is part of the GovLoop Featured Blogger program, where we feature blog posts by government voices from all across the country (and world!). To see more Featured Blogger posts, click here.

I can be a grumpy sort. “Harumph!” could be my middle name. I like to make the distinction between useful and ephemeral technology by emphasizing that ephemeral technology makes 23 year-olds mutter “Keewwll!” as their pupils enlarge, while truly useful technological innovation makes a grey-aired sort like me proclaim “Finally!” (i.e., the technology has successfully addressed an enduring problem, rather than created a solution in search of a problem).

So, i keeping with that perspective, I have to ask “Why on earth does any government *need* that much creativity?”. I’m certainly not arguing against it, but musing aloud about that point where a condiment changes from a wee pile of something at the side of the plate, accompanying and enhancing the main dish, to the meal itself (the way that a 9 year-old might treat catsup).

Maybe the real question to ask is NOT “How can we be more creative, and encourage more creativity?”, but rather “How do we prevent ourselves from not stagnating or getting too rigid? How do we keep ourselves open to useful change when the need arises, and how do we keep ourselves sensitive to when the need has arisen?”.

I would also caution against too much encouragement of creativity, since invariably there will emerge a clash between what employees believe will be valued, and what the organization hasn’t got the time, patience, resources, or flexibility to even begin to consider. And when that happens, you can kiss “engagement” goodbye, and wave to it from the train platform.

I love, and I mean LOVE, this paper: “Diagnosing and Fighting Knowledge-Sharing Hostility” by Husted and Michailova, Organizational Dynamics, 2002, Vol.31:1, pp.60-73. It thoroughly enumerates the many ways, and reasons for, people simply not sharing what it is they or their unit knows. And, as G.I. Joe has affirmed many a time: “Knowing is half the battle”. It is also half of what we conceive of as “innovation” and creativity.

Dean Simonton, at U.C.-Davis, has spent most of his academic career studying creativity; part of that examining “swansong” contributions from eminent people. And while it is true that the counter-intuitive often comes out of the mouths of babes who haven’t been inculcated enough to not be able to think outside the box/lines/received-wisdom, it also comes out of the minds of those with perspective and experience; those who are able to both summarize what has gone on before, yet divorce themselves from it, or think beyond it (and know when they are doing so or NOT doing so).

Maybe the place to start is to ask senior employees “If you had it (your role in this organization) to do all over again, where would you start? Knowing what you know now, what would you do differently?”, making sure to let them off the leash completely.

Our motto is “Innovation… Delivered”; so being creative and innovative is a core competency of the unit. However, as stated by numerous articles in other forums, the federal hiring process imposes restraints that don’t really allow me to seek out and hire creative types. I have to make do with what I have. Some of my employees have grown over the last several years, but I have some that being creative/innovative is just not in their DNA. I can’t fire them or move them to another position, so I work around them. While you can try to foster a culture that encourages new ideas, not sure creativity is something you can teach.

It is indisputable, although I’m sure some would still dispute it, that countries that have some sort of market economy have produced a hugely disproportionate amount of wealth driven by innovation. At some basic level the market mechanism that rewards good ideas is key to translating creative activity into useful products. The omission of competition from this article is glaring. It is hinted at with the mention of risk capital (in scare quotes). How do you measure the ROI on that capital?