When governments invite non-governmental organizations to begin operations in sovereign territory, there are always a series of considerations that emerge in the preliminary negotiations. In anticipating the arrival and implementation of donor funds, the recipient organization/ government has to be aware of the following variables:

When governments invite non-governmental organizations to begin operations in sovereign territory, there are always a series of considerations that emerge in the preliminary negotiations. In anticipating the arrival and implementation of donor funds, the recipient organization/ government has to be aware of the following variables:

- Donor Priorities [interests & goals]

- Conditionality [debt, cash, in-kind, technical, long-term, short-term]

- Local Volatility [political sequencing and electoral cycles]

- Local Modalities [culture and context]

We are accustomed to applauding headlines of aid commitments towards humanitarian causes, and use these announcements to celebrate international coalitions. Headlines such as U.S. to give additional $120 million to help Venezuelan migrants (Reuters, 2019) and U.S. allocates additional $120M after Colombia’s call to step up aid to attend Venezuela migration crisis (Colombia Reports, 2019) are often enough for members of the public sector, academics, and the media to close chapter and move on. This is because a lot of humanitarian aid is still predicated on the measurement of input commitments, and not on efficiency, effectiveness, and output measures.

The science of budgeting has been transforming since the 1960’s, with the fundamental shift being towards the emergence of more performance-based budgeting. Performance-based budgeting relies on a return-on-investments (ROI) approach and can be summarized with the following quotes by the Hoover Commission:

“The whole budgetary concept…should be refashioned by the adoption of a budget based upon functions, activities, and projects; this we designate a ´performance budget´”

– Hoover Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch (1949)

Similarly, Allen Schick, a governance fellow at the Brookings Institute and Professor at the University of Maryland, defined performance-budgeting as “strictly defined, a budget that explicitly links each increment in resources to an increment in outputs or other results.” (2003)

These other results that Schick refers too are of keen application to the science of aid. While input metrics are easy to quantify and therefore easy to present on financial statements, the impact or outcome of said aid can be more difficult to measure.

The science of social impact is strongly correlated with performance-budgeting in that it seeks to measure the correlation between inputs, outputs, and impact in such a way that can objectively reflect the changes connected to a specific intervention. When proposed to the environment of non-governmental organizations and international aid, the challenge is to de-chunk the large bureaucratic structures of these NGOs, and their opaque overhead roots, to better asses outcome efficiency and impact effectiveness.

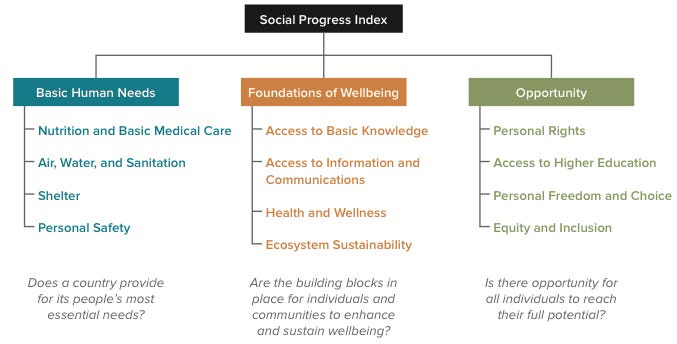

Social entrepreneurs and NGOs operate under the same umbrella goal, which is that of poverty reduction. While most NGOs are fundamentally driven by a global copy-paste model strategy of maximizing humanitarian aid, social entrepreneurs see poverty reduction as a relay of three different stages measure by a platform called the Social Progress Index (SPI).

The SPI is meant to help government bodies identify and adjust priorities based on the underlying conditions and forecast of each situation. The three different stages are:

Stage A: “The capacity of society to meet its citizens’ basic human needs”

Stage B: “Enhance and sustain the quality of their lives”

Stage C: “Create the conditions for all individuals to reach their full potential”

- Eric Carlson, James Koch, Building a Successful Social Venture. (2018)

Each stage requires a completely different set of input requirements, as well as different measurement indicators for output efficiency and impact effectiveness. The one-size-fits-all humanitarian glove, while important for a community or population in Stage A, becomes obsolete and disconnected when the target community transitions into (or begins as) Stage B and Stage C.

While aid continues to be an important component of income for developing nations, it is important that the public sector continues to work with NGOs and the private sector to integrate these new platforms of analysis to better serve the recipient base. This is another example of cross-sector collaboration to promote the effective, yet socially driven, use of resources around the world.

You may also be interested in a former blog entry of mine titled VOLATILE MARKETS, COVID-19, AND THE LAW OF INCREMENTALISM which briefly elaborates on the theory of budgeting.

Enrique Jose Garcia is a GovLoop Featured Contributor. He was born from Cuban parents and was raised in Venezuela until moving to the U.S. to attend university. He has spent most of his career as an entrepreneur in the beverage sector, both in the U.S. and in Cambodia, and most recently started a Master’s at the London School of Economics in Public Administration and concentrating his studies on Social Entrepreneurship. He currently spends his time between London and Colombia and writes for a few publications on economics and entrepreneurship in Latin America.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.