This post is part of a series about the four envelopes that federal IT must “push” to restore public confidence in our capability to deliver superb citizen information technology services.

Having revisited and updated my series detailing the Project Management envelope, we turn now to the second of the four envelopes: Enterprise Architecture – this week’s focus in building a new paradigm for federal IT.

Unlike project management, where the Office of Management and Budget’s Office of E-Government and IT has no foundational roots, federal enterprise architecture stems from the Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996. Despite the heritage, federal enterprise architecture has pretty much died on the vine over the past dozen years.

It didn’t die from lack of leadership: it died from failed execution at the department and agency level. It became just another check-box exercise as part of departmental portfolio reviews. Consequently, over time, less and less qualified staff were assigned to maintaining the architectures at federal departments and agencies, leading to a self-sustaining cycle of diminished importance.

Worse, the foundation on which it is based, the software development lifecycle, has evolved significantly over the past two decades from a rigorously defined set of stages to a much more agile approach to system development, leaving behind much of the ontological structure of enterprise architecture elaboration.

So, the question becomes: How do we fix it?

What It Does

The first step in fixing it is understanding what it’s supposed to do. Enterprise architecture is fundamentally about change management. It starts out by describing where an organization is, strategically and tactically. Then it identifies where the organization wants to go – what it needs to do to meet changing goals, priorities, strategies, and implementing tactics. Finally, it develops plans for how to get from where it is, to where it needs to be: a process-based approach to the essence of change management. The point is that it’s mostly about the organization, not the technology, until you get to the detail level.

The foundation for much of what we now call enterprise architecture can be traced to work by John Zachman while at IBM in the mid-1980s. For the purposes of this “envelope,” it’s important to note that his framework is only ontological. There was no defined methodology attached to the framework.

For the federal government, it pretty much started with the Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996. Along with assigning responsibilities for implementing facets of the act, it established a capital planning regime comparable to what was then commonplace in private industry. Enterprise architecture was to play an important role in directing investments and preventing the building of the same thing in more than one place in the federal government.

The seeds of its own demise were planted early because it telegraphed itself as a “technology thing.” The Clinger-Cohen Act initially was called the Information Technology Management Reform Act of 1996, before it was combined with the National Defense Authorization Act as “Division E.” So instead of assisting with strategic planning, department and agency CIOs often ended up merely documenting strategies already created by senior executives. After all, CIOs were generally not at the table when agency goals and strategies were created (not to mention the criteria by which those executives received their performance awards).

In that process, the only time enterprise architecture came in handy was during IT portfolio reviews. But again, that was purely a technology thing.

How It Does IT

The heart of today’s enterprise architecture design and processes are captured in The Common Approach to Federal Enterprise Architecture and the Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework version 2, developed during the tenure of the man who was at the time the Chief Federal Enterprise Architect of the United States, Dr. Scott Bernard. Author of An Introduction to Enterprise Architecture: Third Edition, Scott laid out the foundation for moving business and technology planning to a strategy-driven, enterprise-level view from the systems and process-level view it then occupied.

To properly introduce how the Enterprise Architecture envelope can fix the problem, let me spend a few minutes introducing you to the Collaborative Planning Methodology and the six related models within the Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework (FEAF).

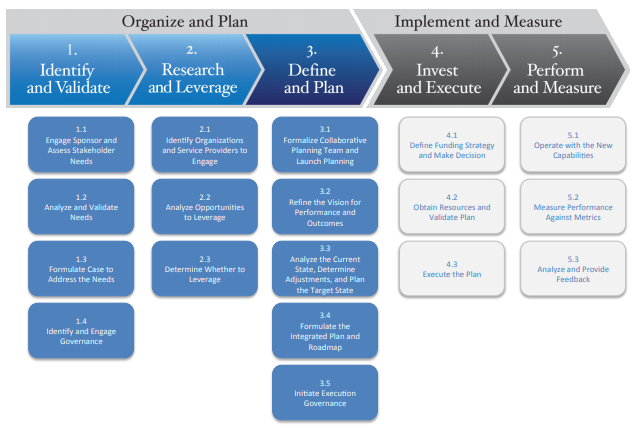

I mentioned earlier that the Zachman Framework did not have a methodology – that it was only an ontology. The missing methodology is provided by the Collaborative Planning Methodology. As shown below, the approach is two-phased and loosely based on standard project management best practices. It is intended to provide a comprehensive lifecycle for all of the scope levels in the Common Approach to Federal Enterprise Architecture.

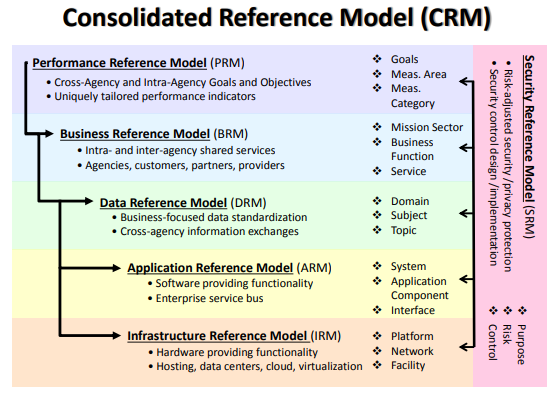

I mentioned the six models within the FEAF. They are (quoted from the FEAF):

- Strategy – which links agency strategy, internal business components, and investments, providing a means to measure the impact of those investments on strategic outcomes.

- Business – which describes an organization through a taxonomy of common mission and support service areas instead of through a stove-piped organizational view, promoting intra- and inter-agency collaboration

- Data – which facilitates the discovery of existing data holdings that reside in “silos” and enables understanding of the meaning of the data, how to access it, and how to leverage it to support performance results

- Applications – which categorizes the system- and application-related standards and technologies that support the delivery of service capabilities, allowing agencies to share and reuse common solutions and benefit from economies of scale

- Infrastructure – which categorizes the network/cloud-related standards and technologies to support and enable the delivery of voice, data, video, and mobile service components and capabilities

- Security – which provides a common language and methodology for discussing security and privacy in the context of federal agencies’ business and performance goals

Each of these models has a “reference model” that provides an elaborate definition and example of what should be in the model. Strategy is contained in what is called the Performance Reference Model while all the others share the names given in the six models listed above. Pictorially, they are shown like this within FEAF with security bracketing all of the layers:

Summary

Now that you have an idea of what enterprise architecture within the federal sector looks like, and before your eyes glaze over with even greater elaboration and additional detail, I need to let you take a break before I go into how we actually push the envelope in enterprise architecture by using tools that make all this manageable and sensible. But that’s next week in Part 2.

A retired naval officer, Richard Warren entered public service in 2009. He holds the PMI Project Management Professional, Risk Management Professional, and Agile Certified Practitioner certifications and currently serves on their Federal Sector Executive Roundtable and other PMI executive roles. He also holds the Federal Acquisition Certification in Program and Project Management at the expert level. He was a founding member of the U.S. Digital Service at the request of the Federal Chief Enterprise Architect and the Obama administration.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.