![]()

I live in the City of New Haven, CT (#gscia). I am reading a super famous book about cities called City by Douglas Rae. It is one of the best books I have ever read.

It has 12 chapters. This is a 12-blog post series about each chapter. This post is about Chapter Three: Fabric of Enterprise.

—

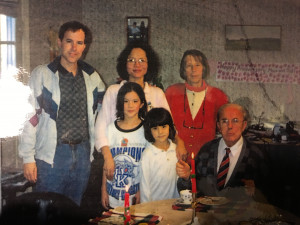

This is my immigrant family.

(I’m the shortest one with the bowl-cut!)

My mom is Korean. My grandparents are British.

They all immigrated to the United States into urban American cities.

Douglas Rae’s City tells the story of the rise and fall of urbanism in American cities. But it’s also the story of immigration in American cities.

Let’s walk-through Rae’s core points on urbanism, immigration’s role in urbanism, and immigration’s role in urbanism in New Haven.

Urbanism

Rae defines urbanism in a few ways, but the definition I’ve been most into is:

“Urbanism accumulated a legacy of habits and expectations for conduct in daily life…They encouraged every household, and nearly every individual, to be an active agent in society, and to do so within the relatively public setting in city life.”

Sounds awesome, right? Rae is describing a time for cities where every individual felt empowered to play an active role politically, economically, and socially to make their community better places to live.

Rae’s theory is that, beginning the 1840, six events happened simultaneously to grow this urbanism to its peak in around the 1920s:

- Steam — A rise in steam-driven manufacturing brought activity to flat water, lowland areas soon to become city hubs (think Providence, Detroit, and New Haven).

- Agriculture — An agricultural revolution allowed food, drink, and clothes to be made in bulk — supporting the needs of more and larger cities.

- Railroads — An integrated railroad system made markets across the country accessible from centralized city manufacturing plants.

- Delayed Rise in Cars — A critical timing gap between the railroad system and automotive transportation allowed for continued centralization of cities.

- Delayed Rise in Distance-Compressing Technology — A delayed implementation of distance-compressing technology, like alternating current (AC) electricity, prevented decentralizing of cities.

- AND (Relatively) Open Immigration: A prolonged period of relatively open immigration allowed for huge growth in individuals in America looking for well-paying, stable manufacturing jobs located in cities.

Immigration’s Role in Urbanism

Between 1871 and 1920, 26.3 million people landed in the United States as immigrants. These 26.3 million flocked to cities — bringing eagerness for sustainable manufacturing jobs, but perhaps more importantly, their variety of talents, customs, and cultures.

This influx of people into American cities was vital. Most simply, there was a match for American cities with well-paying factory jobs and an immigrant population eager to fill them. But more importantly, immigrants from multiple countries brought diverse, inventive retail and small businesses that either became large industries themselves or neighborhood hubs. They lived close to where they worked — using the dollars they earned to contribute right back into local soil at theaters, restaurants, and stores. And individuals became intimately part of the fabric of civic life — becoming elected officials, police officers, artists, and best friends.

Two important notes here:

- Whenever both labor and mass migration are discussed, it is always important to leave space to remember America’s history of slavery. It is reassuring (although I’m admittedly still left questioning) that Rae is explicit that the majority of the immigrant population coming into America at this time had agency.

- In addition, because of laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, most of the immigrant population discussed came from European countries (23.1 of the 26.3 million). Immigration was not accessible to everyone (including, perhaps, members of my own family). Therefore, although this was a time worthy of understanding for its openness and prosperity, it was also a time where immigration was still a deeply broken system.

Immigration’s Role in Urbanism in New Haven

By the early 1900s, the City of New Haven was a true immigrant city. In New Haven, 92,218 of 133,605 residents were either foreign-born or had at least one foreign-born parent.

That means in the early 1900s, 70% of New Haven were immigrants.

At New Haven’s peak of urbanism — a time of social, economic, and political prosperity — a majority of the city were immigrants or from immigrant families. An increased immigrant population wasn’t just a side effect of the rise of urbanism but part of the cause.

And this history remains not just as an artifact but as a living, breathing reality in New Haven. In the past week alone, hundreds of New Haven residents — including elected officials, activists, clergy, police, and students — have filled City Hall, the streets, and campuses to speak, sing, and advocate to protect our city’s immigrants. A lot is at stake: as a sanctuary city, New Haven has up to $56 million in approved and undrawn federal dollars that could be stripped. But New Haven is up for the fight.

Photo by Paul Bass.

As Mayor Toni Harp told a crowd:

“I stand before you tonight urging families to continue sending children to school, urging residents to continue going about their daily routine, and offering reassurance that New Haven remains a safe haven for all who choose to live here.”

This kind of legislation is not unfamiliar in American history — nor are its harmful effects.

In fact, Rae marks the decline of urbanism as also matching fear-based legislation that paralyzed immigration. In the 1920s, the intense negative political reaction against immigration bubbled up to the surface. The Emergency Quota Act in 1921 was passed by Congress that capped legal immigration at 357,802 per year. It also limited any one nationality group to 3% of its representation (according to the 1910 census). And then the Immigration Act of 1924 reduced the quota further to 2%.

This left America more homogeneous — racially and culturally — and effectively diminished any positive effect immigration had on maintaining the of early 1900s urbanism in cities.

—

Rae has helped me put the past week into context.

American cities like New Haven grew and thrived as their immigrant populations swelled. And the benefits brought by immigrants in the early 1900s far exceeded labor — but were more about the creative, rigorous contributions to daily life in our cities.

And just as Rae clearly articulated these benefits, he showed how this can result in fear — and fear-based reaction. We’ve done this before.

The story of our cities is the same story of our immigrants. Both should and will rise — together.

Caroline Smith is part of the GovLoop Featured Blogger program, where we feature blog posts by government voices from all across the country (and world!). To see more Featured Blogger posts, click here.

Awesome, thanks Caroline!

One of the most precious things that immigrants and refugees bring with them is that resource that no nation can do without, or ever have enough of….hope.