In the face of a more globalized and technologically advanced world, the economic and social mandate to understand and speak additional languages has been steadily declining. Regardless of world capital, English is more pervasive than ever. Adding fuel to the uni-lingual fire is technology. Innovations in NLP and machine learning technologies provide near real-time translation capabilities. Inter-galactic space travel may still be a ways off, but we are essentially living in a world with universal translation.

In the face of a more globalized and technologically advanced world, the economic and social mandate to understand and speak additional languages has been steadily declining. Regardless of world capital, English is more pervasive than ever. Adding fuel to the uni-lingual fire is technology. Innovations in NLP and machine learning technologies provide near real-time translation capabilities. Inter-galactic space travel may still be a ways off, but we are essentially living in a world with universal translation.

Despite this trend, there is still value in appreciating other languages. There are hundreds of unique non-English words that are profound and deserved of deeper study. Reflecting on these words is useful because it provides a meaningful switch in what we think about our jobs. For this post, I will start with three Japanese words.

Why Japanese? Well, Japanese was a very popular language to learn in the U.S. not too long ago. In the 1980s, the Japanese economy was truly booming. There was an influx of Japanese tech products in the US. And either driven by fear or greed, there was a dramatic rise in those who wanted to learn the Japanese language. With the Japanese economy no longer booming, the crowds have largely moved on… these days it’s Mandarin.

I personally do not speak Japanese (although I have visited Tokyo). But I find many, many Japanese words transcendental and inspirational – able to inform our daily lives both at work and at home when plain English cannot. In addition, each of the three words below has sizable and meaningful applications to government work and to government workers. If fully embraced by those working to advance agency missions and improve the lives of citizens through technology, I believe these three simple words have the power to transform.

A Beginner’s Mind

“In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, in the expert’s mind there are few.” – Shunryu Suzuki

“In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, in the expert’s mind there are few.” – Shunryu Suzuki

Shoshin is a word originating from Zen Buddhism meaning “beginner’s mind”. Practically, it means looking at the world through the lens of radical openness and complete newness. Just like a child views the world wide eyes and innocently, those who embody shoshin are eager, curious, and unbiased. Imagine putting on a pair of glasses and seeing the world anew.

The benefit of shoshin is that it counteracts the natural tendency to become increasingly closeminded as our level of experience grows. Seen it. Done it. Nothing new to see here. As a result, later in our careers, we rarely truly learn. Instead, we parse information based on our already established perspectives and seek confirmation. We cherry-pick what we hear, what we read, and what we ingest.

Many government workers have been in their jobs or at least working in government for a long-time. The nature of government employment in part is its inherent longevity and the premium placed on tenure. It should not be surprising then that many government staff struggle to see the world around them as new. Everything is colored or tainted by the past. As a result, they unlikely to see the number of new opportunities before them as numerous and plentiful.

Imbibing the “beginner’s mind” is a chance to mentally reset and reflect on what is possible. In a time when we could all benefit from less bias and more learning, we could all do a lot worse than demonstrating a bit of shoshin.

Ongoing, Never Ending Improvement

“The Kaizen philosophy assumes that our way of life – be it our working life, our social life, or our home life – deserves to be constantly improved.” – Masaaki Imai

The purist definition of kaizen is “change for better”. However, its definition has expanded over time. The concept of kaizen became more popular after World War II as part of the rise of the Japanese industrial state. It was a core part of the quality management movement. Specifically, kaizen was a key aspect of the Toyota Way which was emulated by many US manufacturers in the 1970s and 1980s.

In that broader context, its definition has expanded to focus on the ongoing and continuous nature of improvement. It is meant to optimize what already exists. Narrowly, kaizen can focus on a process or system. Generally, it can represent a philosophy.

Embracing kaizen helps to shift the mindset – of the individual, of the team, of the company – from one that is more fixed to one focused on growth. It is a viewpoint that despite how good or how bad a situation is, we have the power to make it better. That nothing is ever perfect, but we can incrementally make it better. It is a foundational belief that every day we have the power to make things just a little bit better today than it was yesterday. And that step by step, we can walk great distances.

The asymmetry of government programs inculcates and reinforces a fixed mindset among workers. Growth and change are risky. To shake free of this anchoring philosophy, government workers should leverage the concept of kaizen to find small, almost invisible opportunities for improvement. This will give rise to slightly larger improvements. Which in turn may lead to sizeable changes. Finding ways to eliminate needless bureaucracy, to foster new ideas, and to eliminate the politics from policymaking can start with micro-actions. That is kaizen.

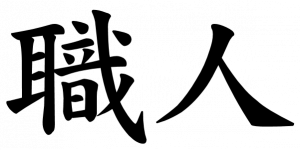

Mastery of One’s Profession

“You must dedicate your life to mastering your skill. That’s the secret of success and is the key to being regarded honorably.” – Jiro Ono

“You must dedicate your life to mastering your skill. That’s the secret of success and is the key to being regarded honorably.” – Jiro Ono

The Japanese place a premium on the apprenticeship model of professional development and learning. This is especially true for endeavors that are artistic or artisan-like in nature. In this way, apprentices are taught the shokunin – the combination of not only the intricate technical skills but also the deeper attitude as it relates to a craft. It may apply to blacksmiths, potters, tailors, or sushi makers (I definitely recommend watching the documentary – Jiro Dreams of Sushi). For the Japanese, becoming a shokunin bestows great honor but also demands great action.

As with shoshin and kaizen, shokunin is a way of life. The spirit of the craftsman is underscored by the belief that there is no shame in any profession as long as it is done with great pride, tremendous care, and it reflects who one truly is. Work done to the best of one’s ability is good work. Period. Unlocking the best of ourselves through our work helps us to find meaning in the work we do. That is the manifestation of shokunin.

There are substantial variations in the work environments in which most government workers spend their time. It is undoubtedly challenging to work with great pride and tremendous care unless the environment supports it. But it is incumbent upon all of us to find ways to seek meaning in our work by doing our best work each and every day.

The process of work is just as important, if not more important, than the outcome (which is often beyond our control.) That is shokunin. The concept of doing one’s job as well as it can be done just because we can will radically alter who we are at work. And potentially alter the impact we have on others through it.

Wagish Bhartiya is a GovLoop Featured Contributor. He is a Senior Director at REI Systems where he leads the company’s Software-as-a-Service Business Unit. He created and is responsible for leading a team of more than 100 staff focused on applying software technologies to improve how government operates. Wagish leads a broad-based team that includes product development, R&D, project delivery, and customer success across state, local, federal, and international government customers. Wagish is a regular contributor to a number of government-centric publications and has been on numerous government IT-related television programs including The Bridge which airs on WJLA-Channel 7. You can read his posts here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.