![]()

I live in the City of New Haven, CT (#gscia). I am reading a super famous book about cities called City by Douglas Rae. It is one of the best books I have ever read.

It has 12 chapters. This is a 12-blog post series about each chapter. Read the other posts in the series here.

This post is on Chapter Eight: Race, Place, and Spacial Hierarchy.

—

Alongside a crew of other activists, I organize New Haven Bike Month.

We are dedicated to pushing for safer streets with biking infrastructure. To reach that goal, we think a lot about two questions:

- Where should we build bike lanes in our city?

- How should those bike lanes be built?

Where should we build bike lanes in our city?

In New Haven (and cities across the country), there’s an idea of who bikes in our cities. They are often white, affluent, and male-bodied. In reality, people of color are the fastest growing population bicycling — with trips by Hispanic, African American, and Asian American individuals growing from 16 to 23 percent of all bike trips in the US (League of American Cyclists, 2013).

This perception gap affects how biking infrastructure resources are allocated — often towards majority white, affluent neighborhoods.

According to Chapter Eight of City, Race, Place, and Spacial Hierarchy, this follows a long history of inequitable resource allocation for neighborhoods in our cities.

Rae outlines three shifts that took place during the twentieth century — all examples of the perils of intersecting policy and bigotry:

Municipal zoning

New Haven adopted its first zoning ordinance in 1926.

Initial residential zoning were some of the first, official attempts at classifying neighborhoods (i.e. Residential A, B, and C; A being preferred). These classifications elevated lower-density, single-family detached housing. They shifted urban spaces away from heterogeneity of uses. Mixed-use neighborhoods with corner stores, retail shops, and multi-family homes — the fundamental facets of city urbanism — were being designated into lower zoning categories implying lower desirability.

And these zoning regulations set the stage for the federal-level neighborhood classifications of the next decade.

New Deal neighborhood security studies

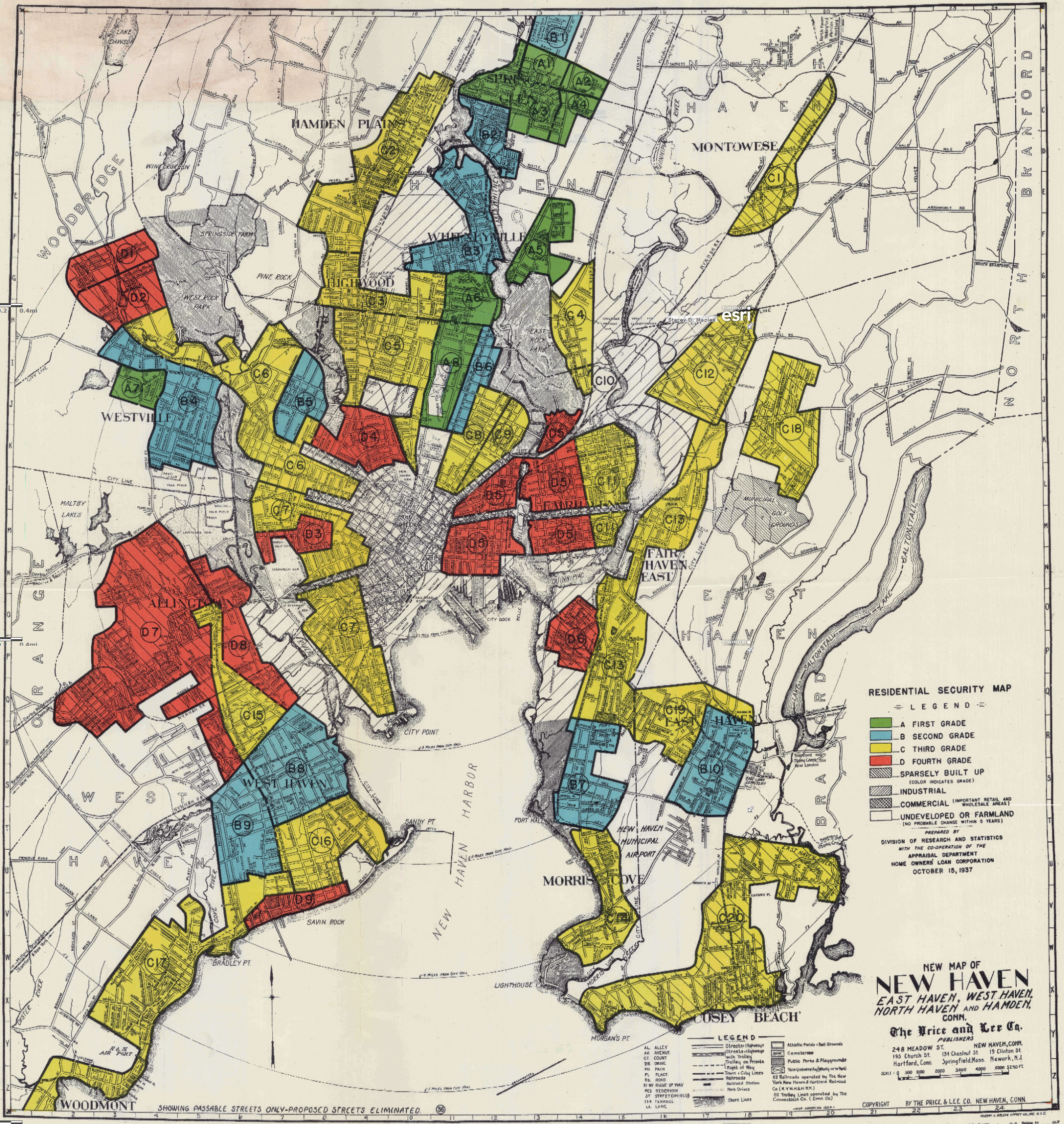

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to protect home ownership in response to the home mortgage market crisis the year before.

In addition to refinancing homes, HOLC produced regional studies of housing markets to determine whether or not neighborhoods were “too risky” to justify investment by private lenders (i.e. banks) to home-owners. These studies evaluated and categorized neighborhoods using both explicit and implicit anti-urbanist and racist criteria – including devaluing neighborhoods because of the existence of old construction, multi-family households, and “lower grade populations” (including individuals identifying as black, foreign-born, or non-WASP).

HOLC map of New Haven. 1937. Photo credit Jonathan Hopkins.

With HOLC’s evaluation of residential security, lenders were advised against investing in neighborhoods with these characteristics — further perpetuating deep resource distribution inequality.

Initial phases of public housing

In 1938, New Haven created the Housing Authority of New Haven (HANH) with $5.5 million devoted to building the city’s first public housing projects.

At first, these public housing projects (Elm Haven, Farnam Court, and Quinnipiac Terrace) were seen as very positive contributors to neighborhoods; they were diverse, with award-winning architecture, with little stigma to being a resident.

“Little or no stigma attached itself to public housing in these early years — years when reliance on public housing was understood universally as a brief phase in a family’s history, followed with any luck by ownership of a private home.” — City, Douglas Rae

Unfortunately, throughout the twentieth century, there was a simultaneous decrease in the city’s available industry jobs and increase in the African-American population in New Haven (and other urban cities) — restricting opportunity for these new families. In addition, investors listened to HOLC’s advice — reducing many African-American families’ available credit necessary for maintenance of their own homes.

With these and other variables combined, low-income public housing had majority African-American populations. And, although it houses many, public housing is often located in places far away from available jobs, leaving many families stuck where they are — just trying to make ends meet.

—

As Rae says about these three shifts:

“All three had at least one consequence in common: to single out what were once thriving working-class neighborhoods and to stigmatize them as inferior to the rest of the city and its region.”

Decades (centuries, really) of these detrimental policy initiatives have led to vast inequality. We need efforts, policies, and initiatives that prioritize equitable resource allocation in our neighborhoods.

New Haven Bike Month’s advocacy initiatives address America’s history of inequitable resource allocation head-on. We aim for an process of advocacy to not only bring more biking infrastructure to New Haven — but more equitable distribution of biking infrastructure.

During New Haven Bike Month 2016, we launched a campaign called 4 Lanes 4 New Haven. It is a call for the City of New Haven to build four protected bike lanes by 2020 — bike lanes that touch every neighborhood in our city.

The goal was to prove to decision-makers that individuals — especially low-income, people of color — also want biking infrastructure in their neighborhoods. Throughout the course of the campaign, we received over 200 pictures of individuals from every neighborhood in New Haven who wanted protected bike lanes in our city.

How should those bike lanes be built?

An equitable approach to resource allocation should not only prioritize where the resources are distributed but how they are distributed.

Residents in neighborhoods are the experts in what resources they need — and, therefore, their voices should be centered.

Through our own experiences and best practices from other cities, New Haven Bike Month has found that through empowering neighborhoods and neighborhood advocates’ voices biking infrastructure advocacy can be sustainable and scalable. For example, local advocates will know best where biking infrastructure ought to be built to create the most impact in the community, resulting in compounding benefits for the community and city overall.

Our approach to this kind of neighborhood empowerment is through Open Streets events.

Open Streets events are neighborhood celebrations where New Haven Bike Month works intimately with neighborhood organizations and residents to close down a street for biking-centered activity. For each event, we forge deep partnerships with local organizations and individuals to organize the event to fit their neighborhood’s unique strengths and needs. During the event, there can be a variety of activities from pop-up bike lanes, BMX bike performances, free bike repair, and more.

Photo credit to Stephanie Upson

These events are meant to give residents in neighborhoods ownership of their streets — through providing resources to design, organize, and attend events themselves.

—

On a personal note, I am grateful for having read Chapter Eight of City. We’re a couple months away from New Haven Bike Month happening in May — and having a deeper understanding of the historical context of our work has both refined and fueled my commitment to and excitement for the work.

Caroline Smith is part of the GovLoop Featured Blogger program, where we feature blog posts by government voices from all across the country (and world!). To see more Featured Blogger posts, click here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.